The ‘Linggadjati Agreement’

- Negotiation table

- Side-table talks

- Sjahrir and Schermerhorn drafting the Agreement

- Schermerhorn and Sjahrir have reached the Agreement

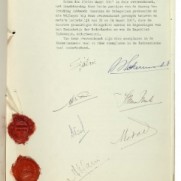

- The Linggadjati Agreement

- House in Linggarjati as it was during the negotiations

- Interieur museum in Linggarjati

Linggarjati is not only the name of a little village on the slopes of the daunting Mt. Ciremai and close to Cirebon in West-Java, but also the name given to an agreement. The Linggadjati Agreement was reached by a Dutch delegation and representatives of the Republic of Indonesia on November 12, 1946 and formally signed in Batavia (Jakarta) on March 25, 1947.

Soon after the capitulation of the Japanese in World War II, the Indonesian nationalists Soekarno and Hatta declared the independence of the Republic of Indonesia on 17 August 1945. This declaration was immediately followed by violent riots (Bersiap period) in which mainly youngsters brutally attacked Dutch citizens. Dutch authorities returning to the Dutch East Indies, soon realized that they were not in a position to restore Dutch authority on Java, Sumatra and Madura, which was controlled by the Republic of Indonesia. In October 1946 they entered talks to put an end to the riots of the Bersiap period.

Lieutenant Governor-General H.J. van Mook (1894-1965), the highest-ranking Dutch administrator in the East, realized that negotiations with Sukarno (1901-1970), president of the Indonesian Republic, were inevitable. However, the Dutch government in the Netherlands, together with most Dutch political parties, was reluctant to talk to Sukarno, especially given his pro-Japanese stance during the war. Under strong British pressure, the Dutch reluctantly started negotiations with the Republic of Indonesia. Van Mook wanted to recognize the Republic of Indonesia as having de facto authority over Java, Sumatra and Madura in exchange for the willingness from the Indonesian side to accept a federal Indonesian state that would be a partner with the Kingdom of the Netherlands. Within the federal Indonesian state the Dutch would at least control Borneo (Kalimantan) and the eastern part of the archipelago.

After the Dutch elections of May 1946, the newly formed Dutch coalition government decided to establish a ‘commission-general’ in order to start negotiations with the Republic of Indonesia. The chair of this commission-general was former prime minister Wim Schermerhorn (1894-1977). The assignment was to adapt the constitutional arrangements for the Dutch East Indies to postwar realities without giving up the Dutch imperial mission. The commission-general left for Indonesia in November 1946 and started negotiations with a delegation of the Republic of Indonesia, which included Sukarno and Sutan Sjahrir (1909-1966), in Linggadjati. Difficult and long negotiations followed on the future relationship between the Netherlands and Indonesia. In the end, van Mook laid down a compromise in which the ‘United States of Indonesia’ to be established by January 1 1949, would become a ‘sovereign and democratic state’ within a Netherlands-Indonesian Union, headed by the then Dutch Queen. The Netherlands-Indonesian Union would concentrate on economic and cultural cooperation. The United States of Indonesia would have three states: the Republic of Indonesia, East-Indonesia, and Borneo. The Dutch would recognize the Indonesian Republic as having all authority on Java, Sumatra and Madura.

Sukarno accepted this compromise in order to avoid a long and difficult armed struggle against the Netherlands and, with the knowledge of his Republic, would control the vast majority of the population of Indonesia and would therefore soon control the United States of Indonesia.

The Dutch commission-general accepted the compromise because a possible war was avoided and a close future relationship between the Netherlands and Indonesia seemed to be assured.

In the Netherlands, conservative forces strongly opposed the Linggadjati Agreement. The commission-general seemed to have “given away” the Dutch East Indies to an irresponsible and unreliable group of Indonesian nationalists. The Dutch government decided to amend and to interpret the agreement in order to assure the Netherlands a reasonable future influence in Indonesia. Parliament passed a motion, by which the Netherlands definitely gave a new interpretation to the Linggadjati Agreement—without changing the precise words of the agreement itself.

Within the Republic of Indonesia, Sukarno faced his own problems in gaining support for the Linggadjati Agreement. Radical elements within Indonesia were supported by the leader of the army, General Sudirman (1915-1950), in opposing the agreement, which did not bring immediate and full independence to Indonesia. However, Sukarno succeeded in convincing the Indonesian Parliament that the Linggadjati Agreement was a stepping stone toward full independence. On March 5, 1947, the Indonesian parliament accepted the agreement, but only with the explicit understanding that the Indonesian government should work toward the ‘liberation’ of Borneo and East-Indonesia by making these areas a part of the Indonesian Republic ‘as soon as possible’.

On March 25 the Linggadjati Agreement was finally signed by the Netherlands and Indonesia in the Rijswijk Palace in Jakarta. In reality, two different agreements were signed. The Dutch signed the agreement as interpreted by the Dutch government and the Dutch Parliament, which meant they agreed on forming a sovereign and powerful Dutch-Indonesian Union in which the United States of Indonesia and the Republic of Indonesia only played a minor role. The Indonesians signed the agreement in its more original form, accepting only a symbolic Dutch-Indonesian Union and wanting a fully sovereign United States of Indonesia in which the Republic of Indonesia would play a dominant role.

This fundamental difference of opinion on the future of Indonesia could not be bridged in the months following the signing of the Linggadjati Agreement. On 20 July 1947 the Dutch government cancelled the accord to commence military intervention against the Republic of Indonesia, hoping ‘moderate’ Indonesians would grasp the opportunity to take over power in the Republic. The Dutch failed to understand that ‘moderate’ Indonesians also desired full independence.

After two military interventions and a prolonged period of dispute and open conflict between the Dutch and Indonesian authorities, the United Nations Security Council established a Committee of Good Offices, which led to the signing of the Renville Agreement in January 1948 on the USS Renville anchored off Jakarta. The international pressure, military failure, and the loss of political influence in Indonesia, made the Dutch accept the independence of Indonesia along the lines of the original Linggadjati Agreement.

In December 1949 the United States of Indonesia was formed, in which the Dutch finally accepted the Independence of Indonesia. The new country was linked with the Netherlands through a symbolic Dutch-Indonesian Union. This political construction only lasted one year: the United States of Indonesia was then replaced by a unitary Republic of Indonesia. Indonesia left the Dutch-Indonesian Union in 1954.

Note by Bapak Umar Hadi*:

Linggarjati is still very well known. Perhaps the older generation has more knowledge than the younger one when it comes to the Linggarjati Agreement of 1946. Through times the agreement has been perceived differently amongst Indonesians, depending the governmental approach.

For those who believe that Indonesia had to secure its independence by means of physical or military struggle, the agreement is often seen as “capitulation”. The perception is therefore negative, as the agreement was seen as retreating from the proclamation of independence of 17 August 1945 by giving up some territories as prescribed in the agreement. This approach was made prevalent in our history books during the Orde Baru era (1966 to 1999) as the government at the time put more emphasis on the role of the military in our struggle for independence.

However, in the Reformasi era today, both political leaders and historians have started to see that the role of diplomatic struggle is as important as the military struggle in securing our independence. The negotiations that took place between 1945 to 1949 are now seen as politically and realistically necessary rather than surrendering to foreign pressures. The Linggarjati Conference is considered important because it was for the first time the young Republic was invited to sit down at the same table with the Kingdom of the Netherlands. Hence, it was actually a de facto recognition of Indonesia as a new state. The Linggajati Agreement should therefore be perceived positively as a strategic diplomatic achievement. Moreover, the Linggarjati Agreement should also be seen in the context of continuous diplomatic struggle in the various negotiations and political debates that include Hoge Veluwe, UN Security Council (the Indonesian Question), Roem-Royen, Renville, and the Round Table.

I believe the new approach will prevail.

*Umar Hadi served the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Indonesia as Consul General of Indonesia in Los Angeles (2014-2017), Director for West Europe Affairs (2012-2014), Director of Public Diplomacy (2005-2009) and Deputy Director at the Office of the Foreign Minister (2001-2005). His overseas posts include Minister Plenipotentiary and Deputy Chief of Mission at the Indonesian Embassy in The Hague, (2009-2012) and Second Secretary at the Indonesian Permanent Mission to the United Nations and other International Organizations in Geneva (1996-2001). He has also been involved in numerous negotiations and international conferences.

Epilogue by Mrs. Joty ter Kulve-Van Os, who’s father Johannes Jacobus van Os built the house in Linggarjati where the Agreement was reached and where she grew up until War II broke out:

Rightly the Indonesians in 1970 have transformed the charming and unique house built in the colonial style of the 1930’s in which the negotiations took place, into a national Gedung Perundingan (museum). The museum is maintained and financed by the Bupati of Kuningan, the regency to which Linggarjati belongs.

See the documentary by Twan Spierts on my visiting Linggarjati

For the Indonesian people the meaning of ‘Linggarjati’ is the fact that there, for the first time in history, both colonizer and colonized spoke on equal terms in an unique meeting. A meeting that was loaded with very sensitive and national sentiments on both sides, also a meeting between different cultures and different religions.

But it was a meeting of real statesmen from both countries, statesmen that were able to surpass their national interests and reached a compromise. They did not realize that the Dutch government and the Dutch people in those days were not matured enough to understand the compromise of the Linggadjati Agreement. Sadly enough this resulted into an Independence War that made hundreds of thousands victims and was followed by the exodus of 300.000 Indische Nederlanders, Ambonesian people and Dutch to the Netherlands, leaving their country of birth.

The initiative of former Minister of Foreign Affairs Bernard Bot in 2005, to represent the Dutch government during the celebration of Independence Day on 17 August – and therewith formally recognize this date (instead of 27 December 1949 as the Dutch authorities had done until then) as the beginning of the Republic Indonesia – after 60 years finally brought the acceptance that the Indonesian people for so long expected.

This achievement resulted in a new, fresh wind in the relation between both countries. The Netherlands-Indies de facto ceased to exist in 1942 when the Japanese took over the colony and the independent Republik Indonesia exists since 17 August 1945 – to all countries.

The stream of Indonesians, students, schoolboys and girls, citizens and politicians, that each year visit the Gedung Perundingan in Linggarjati, underlines its importance. But also many Dutch have found their way the Linggarjati museum. ‘Linggarjati’ became a symbol, one speaks of the ‘spirit of Linggarjati, a spirit of conciliation and good governance. May this spirit be spread throughout the world.